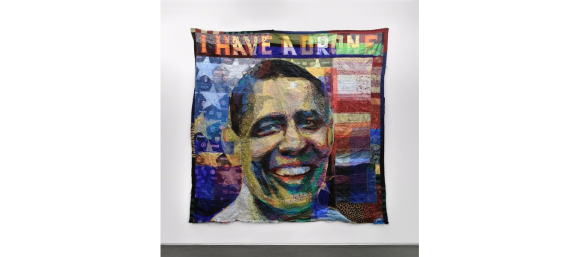

241 × 247.5 cm. Image credits: Galerie Maïa Muller, Paris.

Some nights ago I had the chance to meet Dr. Hassan Musa at SOAS, where he held a conference on the “Mis-connections in contemporary artworlds”. Here is an account of his speech plus the thoughts I flowered mixing this experience with my visit at the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, a couple of weeks ago.

Dr. Musa was born in Sudan in 1951 and now dwells in the South of France. He is an artist, or as he prefers to call himself, an image-maker drawing from a variety of traditions: His most famous works are textiles, linking him with the Sudanese practice of hanging cloths on walls for decorative purposes. He nevertheless uses images from the European painting tradition, and combines them with a witty political discourse conveyed through icons of contemporary times, such as Osama Bin Laden, Barack Obama, Vladimir Putin and so on. He also makes use of elements of Arabic calligraphy as well as Chinese watercolour. All these references are finally tied together by his original research within the technical dimension of the chosen medium.

Valuing curiosity as one of the most important factors in a viewer, Musa feels the technical dimension as a space of total freedom where he can experiment and get to always new ways of fascinating the audience. His use of transparent pieces of fabric, overlapped, glued and finally sewn together is truly skilful; it gives birth to amazing pieces where the delicacy of the medium contrasts with the strong message conveyed by the painstakingly created image.

Interestingly, Hassan contends that nowadays an artist can be vitually anything: There is no proper definition to apply to this term, which has such a disparate application that it has become extremely vague. An artist could be a traditional painter, but also someone involved in a performance of any kind, from a quasi-teathrical installation to a man who let his friend shoot him in the arm, like Chris Burden in Shoot (1971). Therefore Hassan’s preference for the more specific “image-maker” tag. However, if we really want to be specific, even the latter contains a mis-connection: Seeing is certainly a political problem, as what I see may differ from what you see in the same object! An image-maker is thus entangled in a political discourse, in which (s)he will try to make us see what he sees – as in politics.

Not only a problem of terms, mis-connections travel also through the competition between different image-makers using the same image. The use Musa makes of the U.S. dollar, for example, is exquisitely ironic. Some others may nevertheless use that very dollar to create an opposite metaphor. For example:

Hassan is not the first to lament the double conception of history held by the Western culture: Europeans in particular tend to consider the rest of the world as if it didn’t have a history comparable to the one of their geographic region. This bias leads us to see other places as “barbarian”, immerse in a lack of history that is a permanent stagnation. It is easy to spot that this is particulary true in the case of the African continent. Following this view, the advent of European colonialism was a positive event, a fresh start, the redemption of backwards peoples now sharing modernity with and thanks to the magnanimous Europeans… Far from being true, this colonial discourse does not take into account that there is no modernity without freedom. In Musa’s elaboration of the theme, there are therefore two kinds of modernity: the European modernity, embued with colonialist bias; the local modernity, coloured by nationalistic discourses.

However, after the fall of the Berlin wall, Europeans started to question themselves about identity; in the globalized world, we realised that we all share the same destiny. I definitely agree with Musa when he says that the importance given to identity nowadays is the fulcrum of the absurd attempt to categorize artists by their regional origin. So does a fair like 1:54, especially dedicated to “African” art. But the question arises spontaneously and quite simply: What is African art? Or even better: Is there actually something that we can call “African art”? If a Sudanese artist lives and works in France for most of his life, do we still call the result of his artistic effort “African art”?

I think 1:54 is an interesting example of this mis-connection originated by the identity issue. To some extent it also helps another one of the mis-connections Hassan pointed out during his conference: the trauma mis-connection, or the expectation for African artists to have experienced some kind of emotional shock on their arrival to Europe. This organises African art under an umbrella of psychological distress that is completely misleading, and unifies what is in fact a reality of scattered and variegated identities. I can concede that many image-makers nowadays are troubled with the urbanization issue, with all the links to themes like poverty, alienation, technology, pollution, etc. However, this is true not only of artists of African origin – it is a problem that concerns sensible people anywhere. The Contemporary African Art Fair held during the second week of October at Somerset House hosted many works dealing with this theme. But it also gave (rightly) space to other themes. In fact, it is the variety of themes, medias, galleries and artists that makes up the good side of 1:54. Musa strongly affirmed that artists are very individualistic, unless of course they are part of a political discourse – and in that case, most probably, their work is being used to serve someone else’s scope.

This leads us to the last two mis-connections Hassan dealt with at SOAS. First, the diaspora mis-connection, which allows critics to put together all black-skinned artists, no matter where they come from and what their experience is. Second, the curator mis-connection, as curators often are both agents and victims of the other mis-connections considered above. As a result, it is very common to see exhibitions displaying works by artists that come from the most different parts of Africa – grouped together only by the fact that the authors are Africans. As Hassan bitterly remarked, curators often serve their own interests, becoming the real artists behind an exhibition. Curiously enough, a curator is not only someone in charge of a collection, but also, by the law, “a guardian of a minor, lunatic, or other incompetent, especially with regard to his or her property” (see: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/curator).

Art is individual, it is about the singularity of the person. “Africa” is not a good category, neither politically speaking, nor aesthetically, nor philosophically – it is simply a geographic area. The simplicity by which Hassan reminded us that there are no real borders, just political, superimposed, artificial ones, struck me. The question is not, therefore, “Is there an ‘African’ art?” but: What could be a better working term?

Hassan Musa is African as an individual. Nevertheless, he was raised in the European art tradition, because, as he puts it, there is no other History of Art as a discipline. Therefore, he is not an African artist. As Picasso used elements of African art and culture, Musa heavily relies on elements from traditional European paintings. His project as an art-maker clearly unfolds a political dimension. Remaining very realist, he acknowledges that art can’t change the world. But at least it can offer some consolation.

To take the chance and get some relief, you can visit Hassan’s latest solo exhibition in Paris, Yo Mama, at Galerie Maïa Muller, until Nov. 28th.

2008, assembled textiles, 207 x 236cm. Image credits: Galerie Pascal Polar, Brussels.

Useful links:

On Hassan Musa:

Web Site: http://hassanmusa.com/pdf/biography.pdf

Resume: http://hassanmusa.com/pdf/biography.pdf

Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/hassanmusaonline/

Exhibition in Paris: http://www.galeriemaiamuller.com/index.php?idr=7

On 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair: http://1-54.com/london/

Una risposta su “Hassan Musa and the mis-connections within artworlds”

[…] The group of pictures on the Maasai popoulation are maybe separate, an interlude between the many glamorous collaborations this photographer experienced, yet they present the same hieratic power, the same pursuit of a sacred dimension. I don’t know if he would have accepted it, however the characterisation of this trip as his “African period” by the curators reflect the old Western conceptions on Africa as an indifferentiated dark area where mysterious and unintelligible are the key elements. This reiterates a bias that is completely out of date, as discussed in a conference by artist Hassan Musa that I reviewed here. […]

"Mi piace""Mi piace"